The first kind of inflation is what everyone thinks of: banks producing slightly more money than is offset by real goods in the economy, and as a result the prices of goods go up, because the demand of money goes down slightly. Here in Australia we are accustomed to inflation of 2-3% per year, but in many of the "backwards" countries annual rates of 10% or more are normal.

The second kind of inflation also manifests as a price increase, but is not the result of too many dollars printed. If two countries with their own free floating fiat currencies engage in trade, and there is a trade deficit then the currency of the "seller" country will strengthen (their prices will drop lower than what they would otherwise have been because imports will become cheaper) and that of the "buyer" country will weaken (causing imports to become more expensive). This is functionally equivalent to two countries using the same currency trading. Currency will drain out of the buyer country into the seller country, which will be able to buy a lot of goods and services from the buyer country in return.

The third kind of inflation is really just an increase in market price of certain goods due to shortages. For instance, during a famine food prices become extremely high, because people prefer not to starve to death and will pay whatever it takes not to.

Now, I will put it to you that hyperinflation, as I define it, may involve any of those situations but is in fact a separate phenominon altogether.

Investopedia defines hyperinflation as:

Extremely rapid or out of control inflation. There is no precise numerical definition to hyperinflation. Hyperinflation is a situation where the price increases are so out of control that the concept of inflation is meaningless.It goes on to say:

When associated with depressions, hyperinflation often occurs when there is a large increase in the money supply not supported by gross domestic product (GDP) growth, resulting in an imbalance in the supply and demand for the money. Left unchecked this causes prices to increase, as the currency loses its value.Now I mentioned that hyperinflation is a tough nut to crack. Look at what this article on The Library of Economics and Liberty says:

When associated with wars, hyperinflation often occurs when there is a loss of confidence in a currency's ability to maintain its value in the aftermath. Because of this, sellers demand a risk premium to accept the currency, and they do this by raising their prices.

What causes hyperinflations? No single shock, no matter how severe, can explain sustained, continuously rapid growth in prices.That is because the empirical evidence is garbled. Somtimes it is triggered by this, at other times it is triggered by that. Sometimes it happens with mild monetary inflation (my first explanation of inflation) sometimes it is only triggered when that is more severe. It is the wisdom of the Austrian economists in thinking about economics as a deductive discipline rather than an empirical science that leads me to the conclusions I will shortly be mentioning.

First I want to redefine hyperinflation.

Imagine an economy where the entire money supply is $10. Now imagine that the central bank pays its board of two governers $10 each one day, and they go to spend their money. Suddenly the amount of circulating money has increased by a factor of 3, which means that once things stabilise the prices will also be about three times as high as before, in one day. But now imagine the people don't make a stink about this. Maybe they are a very cowed population. This $20 that the two governers can spend allows them to buy pretty much everything, since no one else has anything like as much cash. They buy all the food and products of the entire country. This is an extreme example of the "inflation tax". Monetary inflation results in a slow transfer of wealth from people who get the money last to people who can spend the money first, in this case from everyone else to the two governors. I do not regard this as hyperinflation. It is extremely high inflation in my example, and there are good reasons to believe that this sort of action will cause a hyperinflation episode, but in this case, because the population just allow themselves to be robbed of real goods in exchange for paper money, the "real value" of the money supply remains the same. Everyone's price now becomes three times as high, so life can go on pretty much as it had before.

Now consider a second economy with some amount of fiat money. Again it doesn't matter exactly how much there is, it is all serving to enable trade between people. Let us say that their reserve bank's computers and printing presses are broken and they cannot print any new money for a long time. The supply of the money remains totally constant. Now one day for no specific reason, people begin to question the value of their currency. They start to spend it and buy real goods with it so they won't suffer loss if the currency tanks. As a result of lots of people doing this, the velocity of money is increasing rapidly, leading to rapid inflation. The more prices inflate, the more the money velocity goes up. Pretty soon money is spent as soon as it is earned, and prices are still climbing fast. Not long after this people simply stop accepting the currency. It has become totally worthless. They prefer to look for someone to barter with than to take the currency, because it can only be used as money and now it doesn't even serve that purpose. Now life cannot go on as before, because the "real value" of the entire money stock is now 0. Nothing. No one will accept it as payment for goods or services rendered. This is what I consider hyperinflation. It represents not a rise in prices due to an increase in the money supply but an accelerating and, if not checked, complete loss of confidence in a fiat currency. This causes prices to approach infinity. This grows out of the fourth type of inflation: an increase in money velocity.

Thus: Hyperinflation is a period in which the value of the money stock decreases significantly as people turn to foreign currencies, commodity money and barter to clear transactions.

In the first scenario prices increased extremely rapidly but the value of the entire money stock remained constant. In the second case the money stock remained constant but confidence in it waned and winked out. Since the real value of the money stock goes to 0, it doesn't matter if the central bank prints money. This will keep things going for perhaps a little while longer, but if the note's real value, as seen by everyone, is 0, then it doesn't matter if its denomination is 10 or a googolplex, it just won't be accepted as payment. At this point inflation is effectively infinite, since you can write an arbitrarily large number on the note and it won't be enough to buy a paperclip.

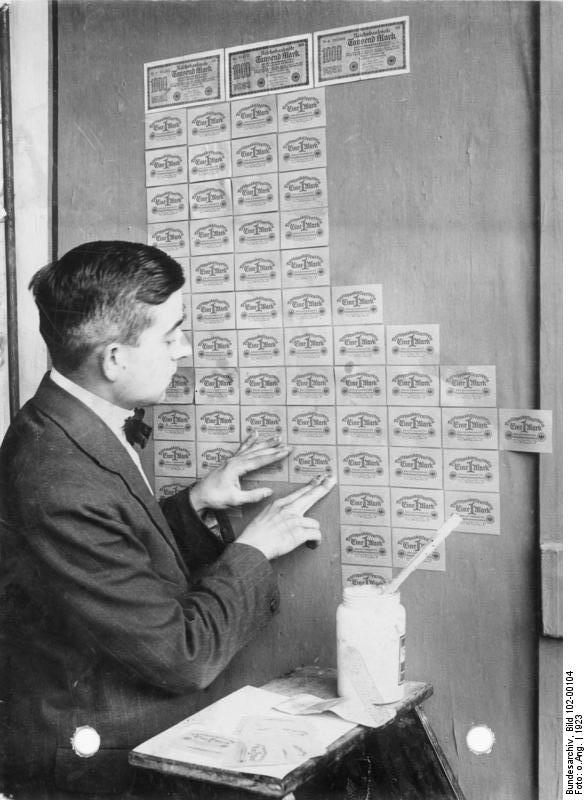

That is not to say that people don't find some use for all the worthless notes:

The chart below shows the official (red) and unofficial (blue) exchange rate of the Zimbabwe dollar with the US dollar during their period of hyperinflation:

This chart has several interesting features. Firstly, the official value of the currency is consistently reported as less than its actual market value. Second, the inflation accelerates insanely fast: look at the vertical axis. The logarithmic scale makes it hard to appreciate just how vertical the line is on the right hand side. It actually bears a remarkable resemblance to another graph I posted on this very blog just a few months back:

This chart has several interesting features. Firstly, the official value of the currency is consistently reported as less than its actual market value. Second, the inflation accelerates insanely fast: look at the vertical axis. The logarithmic scale makes it hard to appreciate just how vertical the line is on the right hand side. It actually bears a remarkable resemblance to another graph I posted on this very blog just a few months back:To create the above chart I exponentially increased the dependent variable while exponentially decreasing the increments of the independent variable it was plotted against. So my pairs were (0,1), (24,2), (36,4), (42,8), (45,16) ... If we turn this situation around and consider the inflation as a simple loss of the real value of the money stock, this later curve becomes a straight line going down from 100% to 0% over the 48 months.

So, to recap: I define hyperinflation as those circumstances where the value of the money stock decreases sharply. This is a psychological phenominon, not a monetary one. If allowed to continue the value of the money stock will go to 0. Typically governments engage in spectacular monetary inflation to try to prop up the ailing currency but this never works, for the reasons I have outlined above. It does result in some pretty interesting banknotes though:

Because hyperinflation is a psychological phenominon its trigger can be hard to pin down. Basically it's anything that causes people to lose faith in the currency, often careless monetary inflation such as Weimar Germany. The trigger for the collapse of the currency rather depends. On a million things. Each situation is unique because all people are unique and the dynamics of the society will affect how the distrust spreads. So in one case it might be so many percent per month inflation that tips the balance, and somewhere else another percentage. Any way you cut it, though, it happens because the currency doesn't have intrinsic worth, and because the currency's production is controlled by a central bank whence the notes must be accepted by the people under pain of fine and or imprisonment.

Hyperinflation can never occur with a commodity money, because if it loses value as a medium of exchange you can use it for other things. Even gold, one of the most useless metals, can serve as pretty nice jewelery and these days we plate quite a lot of it on to electrical connectors to prevent corrosion. Printed paper, on the other hand, is good for nothing but to be pulped and made into toilet paper or charcoal briquettes. It's a pretty slow way of wallpapering your house - though I think it would be worth it just for the conversations you could have - and it doesn't burn that well. Thus if we want to make a currency that is really hyperinflation proof, it has to be on a commodity standard or just be a commodity.

So to answer the question that everyone always asks: can it happen to us. The answer is yes, it can happen to any fiat currency, and because the probability is there, there's every chance that one day it actually will happen, even if we in the Anglophone countries have been spared this pain thus far. Will it happen soon? That's a tough one. I don't think anyone can make that call. It's a divergent condition based on chaotic factors. Impossible to predict. You should be wary if our inflation gets about 10%, though. We're used to 3% and 10% would be a bit of a shocker. Perhaps enough to start driving people away from AUD and into whatever looks juicy at the time. If the reserve bank did insane amounts of quantitative easing that could potentially result in inflation if the banks were to actually lend that money out. Under the current low inflation most people will keep AUD, so providing there's no significant change in the status quo, AUD is safe for now. And because our notes are plastic, if they do lose value you can bung them in the oven and in a few minutes you have some rather fetching earrings, pendants, or mosaic tiles.

No comments:

Post a Comment